"Silk Road", in Chinese sichou zhi lu 絲綢之路, or short silu 絲路, is a designation for the ancient trade routes between China, Central Asia, India, and the Levant. The term was coined by the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen (1833-1905), who used it (in German "Seidenstraße") in his five-volume book on the geography and geology of China, China: Ergebnisse eigner Reisen und darauf gegründeter Studien (Berlin: Reimer, 1877-1912).

The Silk Road itself was first investigated by Albert Herrmann (1886-1945), author of Die alten Seidenstraßen zwischen China und Syrien: Beiträge zur alten Geographie Asiens (Berlin: Weidmann, 1910), Die Verkehrswege zwischen China, Indien und Rom um 100 nach Chr. Geburt (Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1922), Marco Polo: Am Hofe der Großkhans. Reisen in Hochasien und China (Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1924), and Lou-lan: China, Indien und Rom im Lichte der Ausgrabungen am Lobnor (Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1931).

The research of scholars like Herrmann and many others brought to light an immense number of archaeological relics along the Silk Road, mainly in what is today Xinjiang 新疆 (the old Western Territories, Xiyu 西域), and Central Asia.

The Silk Road and the many branches of it, and therefore rather, the Silk Roads, not just served the purpose of trade, but brought together various countries in political, military, cultural, religious, and ethnic matters. Since a few decades the "Silk Road of the Sea" has gained more prevalence in research. Trade was to the same extent conducted through the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean as it was carried out overland.

The most famous part of the Silk Road – and the oldest one that was investigated – is the Oasis Road (lüzhou lu 綠洲路) or Desert Road (shamo lu 沙漠路) that went through the city states of the Tarim Basin. Another, slightly younger, branch crossed the steppe north of the Tianshan Range 天山 and can therefore be called the Grassland Road (caoyuan lu 草原路). Other branches went from southwest China overland to India, crossing the mountainous regions of Southeast Asia today known as Zomia, a term coined by the Dutch scholar Willem van Schendel (b. 1949). This was the Southern or Southwestern Road.

All parts of the Silk Road are revived today to connect China with various parts of the world. This New Silk Road Initiative follows the concept of "one belt, one road" (yidai yilu 一帶一路) that connects the countries of Europe, Asia, and the Near East. The concept of the Silk Road, originally referring to silk trade, is also extended to other products, like porcelain, cotton ("Cotton Road/Silk Road", Dale 2009) or jade, and even adapted to the commercial conquest of the Indian Ocean by European merchants, as in John N. Miksic (2013).

The Silk Road is – as seen from the Chinese perspective – commonly divided into three stages, the first beginning in the Chinese imperial capital Chang'an 長安 (modern Xi'an 西安, Shaanxi) and reaching to the Jade Pass (Yumen Guan 玉門關, close to Dunhuang 敦煌, Gansu), the central stage running through the modern Autonomous Region of Xinjiang, and the western parts extending to India and the Levant.

|

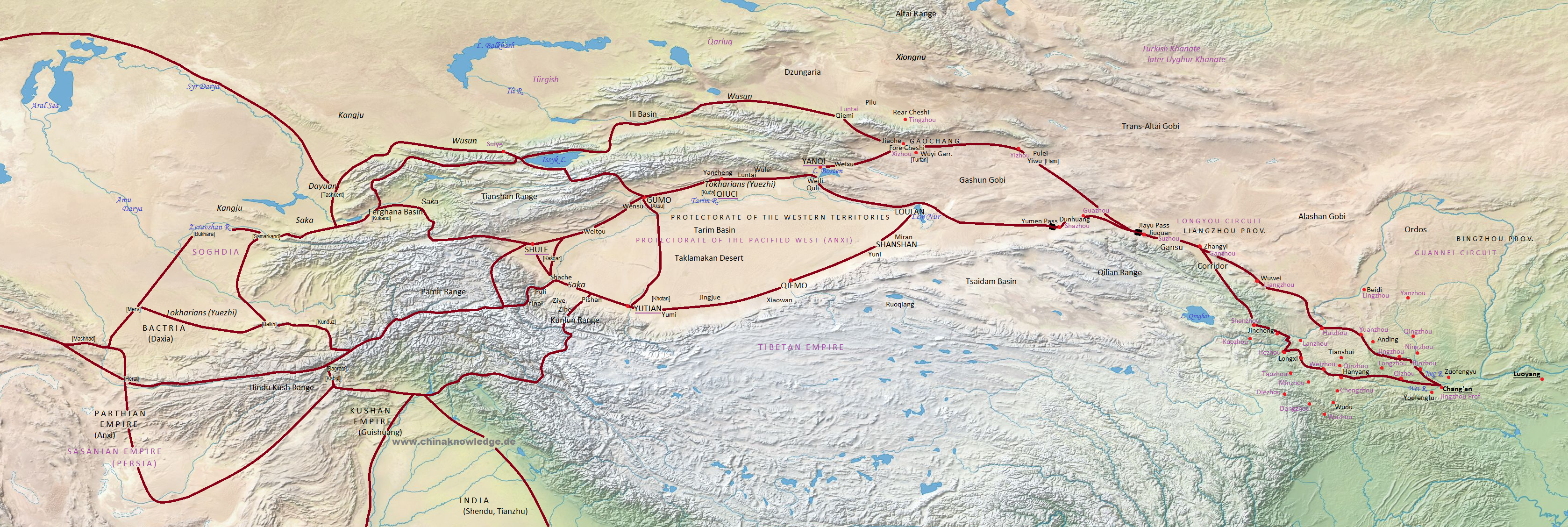

Overview of the Silk Road, the routes on Chinese territory marked with a brown line. Han-period names in black, Tang-period names in violet. Click to enlarge. |

The Silk Road started in Chang'an, in the Later Han period 後漢 (25-220 CE) in Luoyang 洛陽 (today in Henan), and went through the commandery (jun 郡) of Youfufueng 右扶風 upstream River Wei 渭水 – this was the Longshan Route 隴山道. It went on through the mountainous commanderies of Tianshui 天水, Hanyang 漢陽, Longxi 隴西 and Jincheng 金城 (Tang-period prefectures of Weizhou 渭州 and Hezhou 河州). After crossing the Yellow River, and the Silk Road went up the Qilian Range 祁連山 (Tang-period prefecture of Shanzhou 鄯州), and then down into the Hexi Corridor 河西走廊 or Gansu Corridor 甘肅走廊 (modern terms) to the commandery of Zhangyi 張掖 (today in Gansu, during the Tang called Ganzhou 甘州). This was the "Southern Route" (nandao 南道) of the first stage, as seen from Chang'an.

The "Northern Route" (beidao 北道) of the first stage followed the course of River Jing 涇水 through the commandery of Anding 安定 (Tang-period prefectures of Binzhou 邠州, Jingzhou 涇州, Yuanzhou 原州), crossing Mt. Liupan 六盤山, following Wulong River 烏龍河 to the Yellow River (at modern Jingyuan 靖遠, Tang-period Huizhou 會州), and from then on to Wuwei 武威 (during the Tang called Liangzhou 涼州) and Zhangyi.

From Wuwei or Zhangyi, the Silk Road ran through the Hexi Corridor with the commandery of Jiuquan 酒泉 (Tang-period Suzhou 肅州) and the Tang-period prefecture of Guazhou 瓜州 until Dunhuang (Tang-period Shazhou 沙州). This unified stretch is the so-called Hexi Road 河西路. Most spectacular on this section of the Silk Road is the famous Jiayu Pass (Jiayu Guan 嘉峪關), where the Great Wall ended. Another famous point is the "Jade Pass" (Yumen Guan 玉門關 or Yang Guan 陽關) that was considered being the most western point of China proper. It is located just west of Dunhuang.

The middle stretch through the Western Territories was again divided into two different routes. The northern route (Xiyu beilu 西域北道) began at the Yumen Pass, crossed the old city of Loulan 樓蘭 (which vanished in the 4th century CE) at Lake Lop Nur, Quli 渠犁 (today's Korla 庫爾勒), Weili 尉犁 (Karakum), Yanqi 焉耆 (Karašahr), Wulei 烏壘 (Yengisar), Qiuci 龜茲 (Kuča 庫車), Gumo 姑墨 (Aksu), Wensu 溫宿 (Uš 烏什), Weitou 尉頭, and ended in Shule 疏勒 (Kašgar), from where the Silk Road went across the Congling Range 蔥嶺 (Pamir Range) to Persia and India.

The southern route (Xiyu nandao 西域南道) also went across Loulan, its political successor Shanshan 鄯善, Ruoqiang 若羌, Qiemo 且末 (Čerčen), Yumi 扜彌, Yutian 于闐 (Hetian 和田, Khotan), Pishan 皮山 (Guma), Shache 莎車 (Yarkant), and then also traversed the Pamir Range from either Pishan or Shule.

A new northern route (xin beilu 新北路) was opened after Dou Gu 竇固 (d. 88 CE) had defeated the Xiongnu 匈奴 federation in the north. He made possible the opening of the route through Yiwu 伊吾 (today's Hami 哈密, Tang-period Yizhou 伊州) and Gaochang 高昌 (today Turfan, Tulufan 吐魯番, Tang-period Xizhou 西州), from where it liaised with the (old) northern route.

During the Tang period 唐 (618-907), some new routes were opened, one running from Qiuci across Gumo and Wensu, then northwards across the Bada Range 拔達嶺 (western part of Tianshan Range) to Lake Rehai 熱海 (Issyk Gol) and to Suiye 碎葉 (close to modern Tokmok, Kyrgyzstan). From Gaochang on, the route went northwards through Beiting 北庭 (Jimusa'er 吉木薩爾) and Luntai 輪臺 and then westwards through the Ili Valley to Suiye.

Crossing the Pamir Range, the Road went to Guishan 貴山 (today's Khujand, former Kokand), the capital of the Dayuan 大宛 state, then to Kangju 康居 (Samarkand), Bukhara, and then into Persia, by Merv (Mali 馬里 or Mulu 木鹿) and Mashhad (Mashihade 馬什哈德). This city could also be reached through the Alai Plateau and Herat in the former kingdom of Bactria (Daxia 大夏). From Mashhad the Route went to Fandou 番兜 (Hecatompylos, today Saddarvazeh), the capital city of Anxi 安息 (Parthia), and westwards to Ecbatana (modern Hamedan) and Ctesiphon at the banks of River Tigris, close to Baghdad. From there, the way to Seleucia and finally Palmyra (close to Damascus), Antioch or Alexandria (Lixuan 黎軒) was not far.

Travellers going to India had to turn southwards, crossing Xuandu 懸度 (Darel), Jibin 罽賓 (Kashmir) and Wuyishanli 烏弋山離國 (Seistan).

The official dynastic history of the Later Han dynasty, the Houhanshu 後漢書 (47 Ban Chao zhuan 班超傳), lists 36 city states of the Western Territories (Xiyu 西域) that were located along the northern and southern route of the Silk Road. The number later increased to 55 (according to Xie Cheng's 謝承 commentary in Sanguozhi 三國志 7) and even more than a hundred independant polities. During the 3rd century CE, only a few of them were still to be called independant states - these were Shanshan 鄯善 (the former Loulan 樓蘭), Yutian 于闐, Qiuci 龜茲, Cheshi 車師, Shule 疏勒 and Yanqi 焉耆).

There were ten states along the southern part of the Taklamakan Desert (the southern route of the Silk Road), namely: Loulan 樓蘭 (later called Shanshan 鄯善), Ruoqiang 婼羌, Qiemo 且末, Xiaowan 小宛, Jingjue 精絕, Ronglu 戎盧, Yumi 扜彌, Qule 渠勒, Yutian 于闐, and Shache 莎車.

Twelve states were located along the southern flank of the Tianshan Range 天山 and the northern part of the Taklamakan (the northern route of the Silk Road), namely Moshan 墨山 (i.e. Shanguo 山國), Huhu 狐胡, Weixu 危須, Yanqi 焉耆, Weili 尉犁, Quli 渠犁, Wulei 烏壘, Qiuci 龜茲, Gumo 姑墨, Wensu 溫宿, Weitou 尉頭, and Shule 疏勒.

North to the northern route were two larger states, as well as several smaller polities, namely Cheshi 車師 (or Gushi 姑師), Jie 劫, Qiemi 且彌, Beilu 卑陸, Yizhi 移支, Pulei 蒲類, Danhuan 單桓, Yulishi 郁立師, and Wutanzili 烏貪訾離.

Eight states were located in the Congling Range 蔥嶺 (modern Pamir, Kashmir, Hindukush), namely Pishan 皮山, Xiye 西夜, Zihe 子合, Puli 蒲犁, Yinai 依耐, Deruo 德若, Wulei 無雷, Nandou 難兜, and Wutuo 烏托 or Wucha 烏秅.

Some further countries was located beyond the modern borders of the People's Republic of China, namely Juandu 捐毒, Xiuxun 休循, Taohuai 桃槐, Jibin 罽賓, and Wuyishanli 烏弋山離.

These were the basic routes along which the travelers used the Silk Road. It was also possible to reach Yutian from Gumo by travelling along River Hotan across the Taklamakan Desert. In this place, we will not analyse the exact routes through central and western Asia or on the Indian subcontinent.

The most important, yet by no means the only commodity traded along the Silk Road was silk. China was the first country that invented silk spinning. Archaeological discoveries brought to light evidence of 7,000-years old silk spinning, for instance, in silk-patterned incisions on a bone vessel found at the site of the Hemudu Culture 河姆渡文化 in Yuyao 余姚, Zhejiang. Similar finds were made in 1959 in Mei'an 梅堰 close to Wuxian 吳縣, Jiangsu, with black pottery painted with silk patterns. Images of silk cocoons were found in an object in Xiyincun 西陰村 close to Xiaxia 夏縣, Shanxi. Silk-fabric patterns were also found painted on a bamboo case unearthed in Qianshanyang 錢山漾 near Wuxing 吳興, Zhejiang. All these originate in Neolithic sites.

Objects from the Shang period 商 (17th-11th cent. BCE) show fragments of silk fabric. A jade silkworm belongs to the finds from Anyang 安陽, Henan, and the Chinese character for "silk threads" (si 絲) or silk fabric (bo 帛) is found in the oracle inscriptions from that age. The cultivation of mulberry trees to feed silkworms, as well as various techniques of spinning and weaving silk, are mentioned in early Zhou-period 周 (11th cent.-221 BCE) literature like the airs and hymns of the Confucian Classic Shijing 詩經 "Book of Songs". The ritual classic Zhouli 周禮 knows the office of diansiguan 典絲官, a state official who was responsible for the provision of silk fabric to the Zhou court.

Chinese mythology knows stories about the inventors of silk spinning, mainly the deity Lei Zu 嫘祖.

Chinese silk was traded to the steppe as early as the fifth century BCE: It was found in the tombs of Pazyryk close to Novosibirsk, Siberia. Yet silk is also mentioned in the book Arthaśāstra by the Indian minister Kauṭilya (Cāṇakya, c. 350-c.283 BCE), as china-patta. Greek sources from the late 4rd century BCE speak of Σῆρες/Seres as China, σηρικόν/serikon being the Greek word for "silk". The Romans also knew silk as a product of "China" as early as the mid-1st century CE, but they did not know what natural origin the textile had, comparing it, as Plinius the Elder (c. 23-79 CE) did, with cotton, as a botanical produce. Only in the 2nd cent. CE, Pausanias (c. 115-180), described silk as the product of silkworms. The mysteries of silk production remained secret to the Romans for long. Only from the 6th century on, silk was produced in Byzantine.

The first traders in silk were quite probably the central Asian tribes of the Saka (in Chinese Sai 塞) and the Tokharians (in Chinese Yuezhi 月氏), who lived in what is today Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

Another route was through southwest China, where the tribes of the Dian 滇 did not allow merchants of the Han dynasty to pass through.

The attested history of the Silk Road begins, from the Chinese side, with the mission of Zhang Qian 張騫 (164-114 BCE) to Central Asia in 139 BCE. He had been sent out in search for allies against the steppe federation of the Xiongnu that dominated the northern borders of China and controlled the trade routes of the northwest. Zhang visited the lands of the Tokharians and the Dayuan in the Ferghana Basin. He did not find allies against the Xiongnu, but helped to create trade relations with Han China.

The inhabitants of the Han capital Chang'an were interested in exotic products, too. From 121 on general Huo Qubing 霍去病 (140-117 BCE) carried out several campaigns against the Xiongnu and ended their domination over the city states of the Tarim Basin. He initiated the creation of several commanderies in the northwest (Jiuquan 酒泉, Zhangyi 張掖, Dunhuang, and Wuwei 武威), regular administrative units that made this region part of China proper.

In a second mission to the tribes of the Wusun 烏孫 and the city states, Zhang Qian succeeded in suggesting several dignitaries to visit the Han court in Chang'an. In 104 general Li Guangli 李廣利 (died 88 BCE) defeated the Dayuan and subjected all polities in the west. In 60 BCE the Protectorate of the Western Territories (Xiyu duhufu 西域都護) was created, which formed the political basis for the large economic exchanges that took place from then on.

Not even the turmoil at the end of the Former Han and the creation of the Later Han put a real end to this "early globalization". Ban Chao 班超 (32-102 CE) restored the suzerainty of Eastern Han China over the Western Territories. In 97 CE a mission was sent to the country of Daqin 大秦, which is commonly interpreted as the eastern parts of the Roman Empire, or Syria. The nobility in the Mediterranean, not knowing how to produce silk, was enthusiastic about this type of textile, and Roman writers lamented on the tremendous expenditure spent to buy foreign luxury goods as silk. The Roman purchase of silk and other Oriental commodities was so huge that contemporaries feared the drain of gold and silver to the Orient. Later Han-period tombs unearthed in Xinjiang indeed proved how important silk was as a commodity, and even for daily use of the local population.

After the demise of the Han dynasty, China was for three centuries (most of the time at least) divided into several states. Even if the Chinese demand for foreign luxury goods was not as great any more as during the Han period, the rulers of the north, like the Former Liang dynasty 前涼 (314-376), did all they could to foster good trade relations with the states and tribes in the northwest.

During this time, more and more Buddhist monks arrived in China and helped to make their religion part of the landscape of Chinese religions.

The reunification of China under the Sui 隋 (581-618) and Tang dynasties revived the trade routes and gave the impetus for an even more intensive exchange. Again, the Western Territories were politically secured by China in the Protectorate of the Pacified West (Anxi duhufu 安西都護府). There was a huge demand for foreign products, foreign singers and dancers, and also for foreign pastoral care, as new religions arrived in China with the creeds of Nestorianism, Zoroastrianism, and Manicheism.

The most important merchants trading with China were the Soghdians, many of whom lived for generations in the capital Chang'an and other cities in Tang China. The demand for exotic luxuries in Chang'an is described by Schafer (1963). Tang-period literature gives a brilliant picture of the cultural and economic exchange that took place in the 7th and early 8th centuries.

Two events ended this brilliant age of the Silk Road. The first was the rebellion of An Lushan 安祿山 (703-757) in the mid-8th century that devastated Chang'an and weakened the Tang dynasty financially. The second was the northward expansion of the empire of Tubo 吐蕃 (Tibet) that conquered the access routes along the Gansu Corridor and also part of the Western Territories. As one result of these occurrences, the southern part of the Silk Road was blocked, and therefore the northern one won prominence. It went through territory controlled by various Uyghurian tribes, and is therefore called the "Uyghurian Road" (Huihu dao 回鶻道).

After the tenth century, the political and economic centre of China shifted to the southeast, so the sea route became more important. Indian, Persian and Arab traders dominated maritime commerce in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. They were only gradually displaced by European traders with their huge vessels in the sixteenth century.

Northern China was controlled by various states, first the Five Dynasties 五代 (907-960), then the non-Chinese dynasties of the Western Xia 西夏 (1038-1227), Liao 遼 (907-1125), and Jin 金 (1115-1234). The Silk Road through Central Asia never disintegrated during that age, but the trade volumes were far smaller than during the Han and Tang periods.

The Silk Road experienced its last apogee under the rule of the Mongols, when the creation of regular postal stations or caravanserais under the so-called "Pax Mongolica" (in analogy to the Pax Romana) allowed free movement of merchants. The most famous example of trade during that age is the Venetian Polo family, a scion of which, Marco, stood in the service of the Great Khan and was in possession of a tally allowing him to move freely to all parts of the Mongol empire.

Envoys, missionaries and merchants travelled from Europe or the Levant to the khan's court in Mongolia, or to the prosperous cities in the southwest, like Hangzhou 杭州 (by Marco Polo called Quinsai).

Not for the first time, trade exchange over long distances led to a movement of bullion from one part of Eurasia to the other. Silver, arriving to China from the west along the Silk Road, played an ever more important role in the Chinese monetary system.

The Silk Road as a single, unified trade network from China to the Levant was ended after the withdrawal of the Mongols into the steppe and the foundation of the Ming dynasty 明 (1368-1644). Even if one cannot speak of a real seclusion policy as in the case of Japan between 1600 and 1850, the Ming dynasty carried out a trade policy in which the government was not involved, and for many decades even forbade naval trade at all. The only exception of this general rule were the famous naval expeditions of Zheng He 鄭和 (1371-1433), who several times visited, in the name of the Ming court, countries in Southeast Asia and even at the African coast. His voyages would not have been possible without the existence of well-known maritime trade routes.

The Qing dynasty 清 (1644-1911) followed this paradigm and restricted foreign naval trade to the port of Guangzhou 廣州 (the Canton System). Even after having conquered the Western Territories - in the meantime thoroughly Türkicized and therefore often called "Eastern Turkestan" - and renaming them Xinjiang "New Domains", the Qing did nothing to revive the ancient Silk Road, and perhaps, the political situation in Central Asia did not allow.

Another reason for the missing revival of the Silk Road might be that by 1700, the consumers in Europe either drew their products from other sources (the Americas) or had discovered new, faster, and more profitable ways of transport (shipping). Finally, the Chinese demand for foreign products had declined, and as "conservative consumers", neither the state nor the population were interested in promoting foreign trade. On a small scale, the caravan trade in Central Asia (e.g. bringing tea to Russia) continued, and on the South China Sea, private traders made their way, but not, as before, the government.

Persia was the most important consumer of Chinese products, ranging far above Rome. During the early Tang period, no less than 23 official trade missions came from Persia to China, and 31 from Dashi 大食, which was a general term referring to countries in Western Asia. The most important trading nation were the Soghdians, living in what is today Uzbekistan. Soghdian merchants (shanghu 商胡 "merchant barbarians") had trade posts in many cities of China, and the Near East. Apart from the Soghdians, the nomad tribes of the Xiongnu, Tujue 突厥 (Türks), and the Uyghurs (Huihu 回鶻), as well as the inhabitants of the many oasis city states of the Western Territories controlled the trade along the Silk Road.

The conflicts between the Chinese Empire, the nomad states, and the city states revolved around the control of the trade routes. The Xiongnu threatened Chinese border towns and pressed out of Han China not only princesses (see marriage policy heqin 和親), but also grain, horses and silk. From the late Tang period on, tea also became an important commodity required by the steppe peoples, and also lacquer products and porcelain. The Chinese for their part could obtain horses and iron products, for which the nomad tribes were famous. Part of the Silk Road network was therefore known as Tea-Horse Road (see tea-horse trade).

Silk was such an important commodity that it even served as a kind of money in the western parts of China. China imported agricultural produce as medicago (musu 苜蓿), pineapples (boluo 菠蘿), sugarcane, grapes, sesame (huma 胡麻 "barbarian hemp"), vicia beans (hudou 胡豆 "barbarian beans"), or walnuts (hutao 胡桃 "barbarian peaches"), or domestic animals, and also gold and silver artwork, woollen textiles, gems, fragrances, jade or glass.

In the cultural sphere, China received influences of Indian art (joined to the iconography of Buddhism), and Indian and Persian music (huyue 胡樂, husheng 胡聲 "barbarian sounds"), for instance, tonal systems and new musical instruments like lutes and fiddles, and also artistic performances as dance and theatre. In the range of Tang court music, for instance, non-Chinese plays occupied half of the portfolio at the court. This cannot only be attested in literary sources, but also in archaeological finds of handicraft objects – which show clearly Western Asian influence -, wall paintings, Buddhist statues, or ceramic figurines.

The polo game (maqiu 馬球) had also come to China during the Tang period. Painters and sculptors from Khotan (Yutian) served the Tang emperors, with famous names as Yu-chi Ba-zhi-na 尉遲跋質那 and his son Yu-chi Yi-seng 尉遲乙僧 (Viśa Īrasangä), Tan-mo-zhuo-yi 曇摩拙義 or Kang-sa-tuo 康薩陀. Their "relief paintings" (aotuhua 凹凸畫) had their origins in India. Buddhist believers sponsored the creation of caves (shiku 石窟) with statues and wall paintings.

The book catalogues of the Tang period record quite a few titles on Indian medicine. Even if the Chinese calendar had been the object of constant research since oldest times, the calendric system of India attracted great attention in China. Thus Qu-tan-luo's 瞿曇羅 calendars (Jingweili 經緯歷, Lindeli 麟德歷) were well known in Tang China, as well as the Jiuzhi Calendar 九執歷, and the monk Yixing's 一行 (683-727) Dayan Calendar 大衍歷.

Buddhism came to China along the Silk Road, but Buddhist missionaries also arrived across the sea. During the Tang period Buddhism had become a distinct part of the religious landscape and had adopted genuinely Chinese characters. It influenced the native religions of Daoism and Confucianism. Apart from Buddhism several other Western Asian religions came to China, like Zoroastrianism (xianjiao 祆教), Nestorianism (jingjiao 景教), and Manicheism (monijiao 摩尼教), and finally also Islam. Like Buddhism before, these religions spread to communities in the whole territory of China – yet on a much smaller scale than Buddhism.

From the 12th century of Franciscan priests like Giovanni da Pian del Carpine (c. 1185-1252), Willem van Rubroeck (c. 1220-c. 1293), Giovanni da Montecorvino (1247–1328) or Odorico da Pordenone (1286-1331) travelled along the Silk Road. One of the last visitors going to China was the Maroccan traveller Ibn Baṭūṭah (1304-1368). He visited Persia and India, but arrived in China by sea.

There were also travels in the opposite direction, mostly of Buddhist monks going to India, like Faxian 法顯 (337-422) or Xuanzang 玄奘 (602-664), and much later, Rabban bar Sauma (c. 1220-1294), a Nestorian priest, who went as far as Rome and Paris. He wrote a diary that is preserved in Persian language. This narrative is the only one of its time that provides an East-Asian perspective on the Silk Road and on European ways and trade.

Chinese achievements travelled westwards. Apart from silk, the major innovations of paper, printing, gunpowder, the compass, and porcelain making, spread to the west. Yet with the ready-made silk products, the techniques of rearing silkworms, spinning and weaving came to the city states in the Western Territories, and from there, the "secret" of silk migrated westwards. Around 300 CE it was known in the Western Territories, and in the 7th century in the Levant. Paper is believed to have been transmitted to the Levant after the battle at the Talas (Daluosi 怛羅斯) in 751, after which the Arabs conquered Central Asia and abducted Central Asian craftsmen, who knew the secret of making "paper of Samarkand".

The intensity of trade allowed all cities and countries for economic prosperity. This is also true for the westernmost regions of China with the many oasis cities inmidst of a barren landscape.