The Queen Mother of the West (Xiwangmu 西王母), abbreviated to Queen Mother (Wangmu 王母), also called Golden Mother (Jinmu 金母) or Primordial Lady Golden Mother (Jinmu Yuanjun 金母元君), and in vernacular context Aunt Queen Mother (Wangmu Niangniang 王母娘娘), was originally a legendary female deity and later became part of the Daoist pantheon, having a leading position among the "immortals".

The name Queen Mother of the West is first seen in the bizarre geography Shanhaijing 山海經 that came into being in the Warring States 戰國 (5th cent.-221 BCE) and the early Han period 漢 (206 BCE-220 CE). The section on the "Western Mountains" (Xishan jing 西山經) says that she lived on Mt. Jade (Yushan 玉山), had the body of a human person, but a leopard's tail and fangs like a tiger. With the help of a herb of immortality she presided over the "catastrophes of the sky" (tian zhi li 天之厲) and the five destructive forces (wu can 五殘). She also wore a victory crown (dai sheng 戴勝) over her tangled hair. Another section of the book, that on the "Great Western Wilderness (Dahuang xi jing 大荒西經), she was said to live on Mt. Kunlun 崑崙 between the Red River 赤水 and the Black River 黑水. The section on the Northern Region within the Seas (Hainei bei jing 海內北經) further explains that the Queen Mother leaned against her raised seat, wore a victory headdress and hold her staff. There were three green birds (san qing niao 三青鳥) which gathered food for her. It seems that she was originally a dangerous and inauspicious character.

|

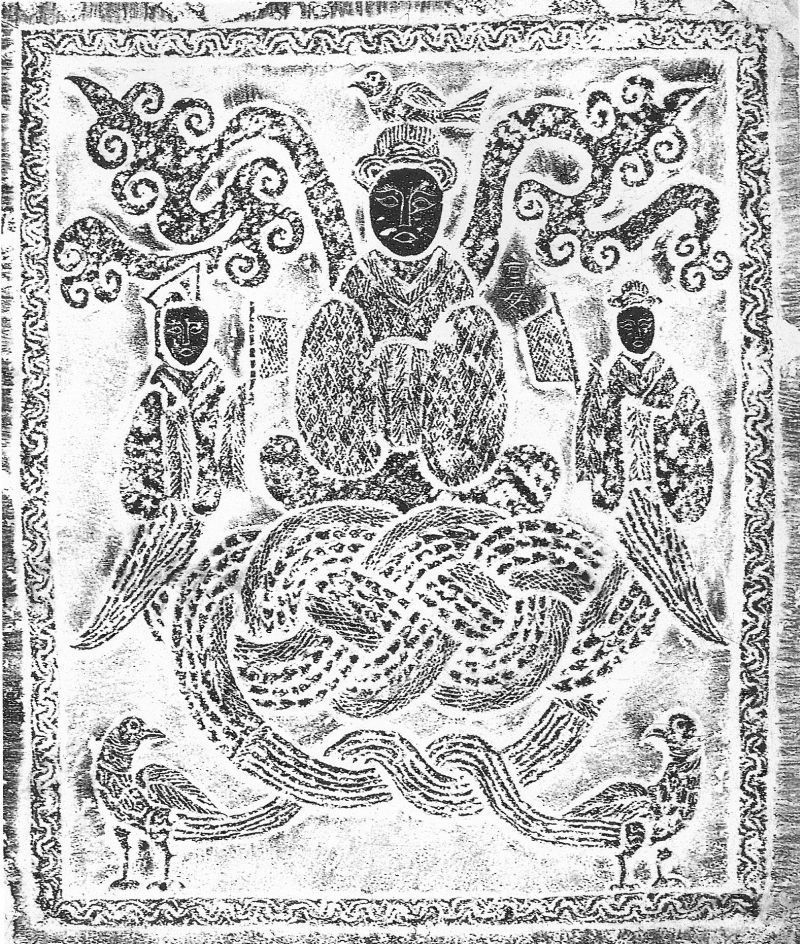

Rubbing of a stone relief from the Han period, showing the Queen Mother sitting on her throne. To her head, a bird is seen, and clouds emerge from her shoulders. She is flanked by two persons, whose very long snake-like tails are twisted and end in two birds, standing in the lower two edges of the image. Even if only the name of the Queen Mother is written down (just to the right of her figure), the two others must be Fu Xi 伏羲 and Nü Wa 女媧. 56 × 67 cm. Unearthed in Liangcheng 兩城鎮 in Weishan 微山, Shandong, and kept in the Museum of Weishan (Weishan Wenhua Guan 微山文化館). Source: Zhongguo meishu quanji bianji weiyuanhui 《中國美術全集》編輯委員會, ed. (1993). Zhongguo meishu quanji 中國美術全集, Huihua bian 繪畫編, Vol. 18, Huaxiangshi huaxiangzhuan 畫像石畫像磚 (Shanghai: Shanghai renmin meishu chubanshe), no. 37. |

|

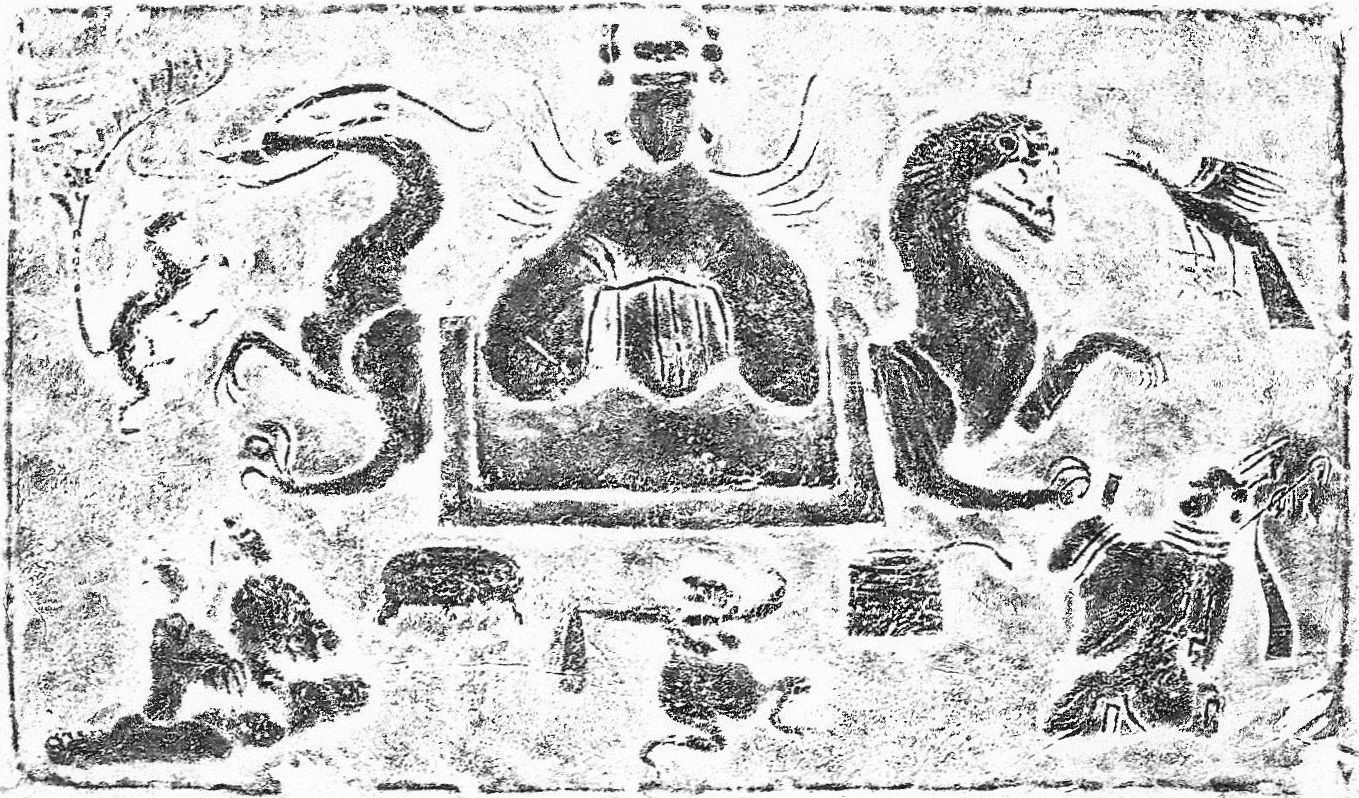

Rubbing of a brick relief from the Han period, showing the Queen Mother sitting on her throne. To her right hand, a nine-tailed fox (jiuwei hu 九尾狐) and a dragon are facing each other, and to her left, a three-legged crow (sanzu wu 三足烏) and a tiger are facing each other. Just in front of the Queen Mother, a toad is dancing (see the story of Chang E 嫦娥), while male and female onlookers (immortals?) are sitting to the right and left sides of the scene. 28 × 49 cm. Unearthed in Xinlong 新龍鄉 in Xinjin 新津, Sichuan, and kept in the Provincial Museum of Sichuan (Sichuan Sheng Bowuguan 四川省博物館). Source: Zhongguo meishu quanji bianji weiyuanhui (1993), no. 216. |

In contrast to that, the early Han period book Huainanzi 淮南子 describes her as an auspicious immortal who had won eternal life with the help of a herb. The commentary on the text Ji Yan Guanglu wen 祭顏光禄文 in the anthology Wenxuan 文選 quotes from an old divinatory text called Guicang 歸藏, where it is said that the moon fairy Chang E 嫦娥 had been presented the herb of immortality by the Queen Mother of the West, and was so able to ascend to the moon.

The Huainanzi (chapter Lanming 覽冥篇) also refers to this story, but includes the character Yi 羿 in the tale who was the husband of Chang E.

In 279 CE a chronicle was unearthed, the Jizhongshu 汲冢書 (later known as the "Bamboo Annals"), as well as the pseudo-biographical book Mu Tianzi zhuan 穆天子傳 of the travel of King Mu to the west. According to these books, the Queen Mother of the West came to the court of the kings of the central states, and was hosted before travelling back to Mt. Kunlun. King Mu in turn visited her on his journey. On that occasion she granted the King immortality.

The feature of immortality, owned by the Queen Mother herself, is also mentioned in the Daoist book Zhuangzi 莊子 (chapter Dazongshi 大宗師).

By the beginning of the Common Era, the Queen Mother was seen as an immortal, like in the rhapsody Daren fu 大人賦 by Sima Xiangru 司馬相如 (179-117 BCE), where she is described as a person with whitish hair, or in Yang Xiong's 揚雄 (53 BCE-18 CE) Ganquan fu 甘泉賦, where she is perceived as a kind of deity of immortality.

Historiographical sources in the official dynastic history Hanshu 漢書 mention that in a case of draught in 3 BCE, the population produced prayer tablets invoking the help of the Queen Mother (Xiwangmu chou 西王母籌) that were distributed everywhere, and the people assembled in front of the shrines dedicated to her where dances were performed to appeal to her for support. A similar account is found in the Daoist scripture Taipingjing 太平經. It seems thus that the Queen Mother had not fully lost her inauspicious character.

The Western Jin period 西晉 (265-316) collection Bowuzhi 博物志 by Zhang Hua 張華 (232-300) includes a story said to have taken place during the reign of Emperor Wu 漢武帝 (r. 141-87 BCE) of the Han dynasty. The emperor was in search for immortality, when the Queen Mother sent an embassy presenting white deer to the emperor. He banqueted them, and in the night of the 7th day of the 7th month, the Queen Mother herself appeared, accompanied by three blue birds which waited upon her. She took out seven peaches and gave five of them to the emperor. He ate them and carefully laid the stones before his knees. Sweet as the peaches were, he desired to plant the stones. Seeing this, the Queen Mother laughed and explained that it took three thousand years for one peach to grow.

This story was later adapted in the collection Han Wudi neizhuan 漢武帝内傳 and expanded to a lengthy description how the Queen Mother taught Emperor Wu the way of becoming an immortal. She was herself a disciple of the Celestial King of the Primordial Beginning (Yuanshi Tianwang 元始天王). In her instructions, she warned the Emperor to indulge in sexual pleasures, and handed over to him the Diagram of the True Shape of the Five Summits (Wuyue zhenxing tu 五岳真形圖) and the scripture Lingguang shengjing 靈光生經 "Book of the life of the numinous brilliance", as well as twelve other scriptures or talismans (including Liujia zuoyou lingfei fu 六甲左右靈飛符).

The names of these writings and documents prove the influence on the Shangqing School 上清派 on this story. Another support for this thesis is the figuring of the Yuanshi Tianwang, who was the highest deity of early Shangqing Daoism. This can be proved in Tao Hongjing's 陶弘景 (456-536) Zhenling weiye tu 真靈位業圖 "Diagram of the positions of the perfect numina".

Ge Hong's 葛洪 (283-343 or 363) description of deities, Yuanshi shengzhen zhongxian ji 元始上真眾仙記 (also known as Zhenzhongshu 枕中書), explains that when Yin and Yang (er yi 二儀) were not yet separated, the Yuanshi Tianwang floated in-between them. When the separation was fulfilled, he "penetrated all energies and joined all essences" (tongqi jiejing 通氣結精) with the Holy Mother of the Grand Origin (Taiyuan Shengmu 太元聖母), and they produced the "Eastern King-Lord, Great Emperor Supporting the Mulberry" (Sangfu Dadi Dongwanggong 扶桑大帝東王公) and the "Mysterious Maiden of the Nine Brilliances" (Jiuguang Xuannü 九光玄女), who was no one else than the Queen Mother of the West. Both reigned in the Kunlun Range, where all immortals assembled for court audiences thrice a day. It can be seen that the status of the Queen Mother rose continuously.

The register Shangqing yuanshi bianhua baozhen shangjing jiuling taimiao guishan xuanlu 上清元始變化寶真上經九靈太妙龜山玄籙 further elaborated stories about her and alleged that her personal name was Wanjin 婉衿, and that she was bestowed by the Yuanshi Tianwang the title of "Immortal Mother of the Supreme Truth of the Nine Numinosities of the Western Origin" (Xiyuan Jiuling Shangzhen Xianmu 西元九靈上真仙母). Her residence was the Jade Pond (Yaochi 瑶池) on the Hill of the Western Tortoise (Xigui zhi yue 西龜之岳). Her duties were to keep registers of the immortals there and to spread the "jade purity" (yuqing 玉清). Three times in a month she ascended to the Jade Purity Heaven, held banquets on Mt. Kunlun and instructed the immortals. The Queen Mother was wearing a lavishly decorated court robe as signs of her official function in the Daoist heavens. Her purple chariot was drawn by phoenixes, and she was waited on and guarded by seven hundred jade girls (yunü 玉女).

The imagination of an eternal banquet was described in the book Zuanyilu 纂異錄, which is quoted in the encyclopaedia Taiping guangji 太平廣記. Persons from thousand years of history took part in this festivity.

The late Tang period 唐 (618-907) book Yongcheng jixian lu 墉城集仙錄 by Du Guangting 杜光庭 (850-933) is a kind of resummee on all various beliefs about the Queen Mother. The "biography" (zhuan 傳) of the Golden Mother narrated there is also found in the Daoist encyclopaedia Yunji qiqian 雲笈七籤 and the Taiping guangji, and in short form also in the biographic collection Jixianlu 集仙錄.

These various stories show that the status of the Queen Mother was just second to the Three Pures (Sanqing 三清), the highest deities in the Daoist pantheon. She was therefore given various epithets, like Immortal Mother of the Supreme Veracity of the Nine Numina from the Western Origin (Xiyuan Jiuling Shangzhen Xianmu 西元九靈上真仙母), Queen Mother of the West of the Utmost Veracity, with the White Jade, the Tortoise Terrace and the Nine Phoenixes (Baiyu Guitai Jiufeng Taizhen Xiwangmu 白玉龜臺九鳳太真西王母), Golden Mother of the Tortoise Hill of the Utmost Miracle of the Nine Numina (Jiuling Taimiao Guishan Jinmu 九靈太妙龜山金母) or Primordial Lady, Golden Mother of the Tortoise Hill of the Nine Radiances of the Utmost Numina (Tailing Jiuguang Guitai Jinmu Yuanjun 太靈九光龜臺金母元君).

The Queen Mother was not included into the Daoist liturgy before the Southern Song period 南宋 (1127-1279). She is mentioned in Zhong Li's 仲勵 (early 12th cent.) liturgical register Qisi baizhang da jiaoyi 祈嗣拜章大醮儀 in the 20th psoition. The list of 360 deities in Jin Yunzhong's 金允中 (c. 1200) Shangqing lingbao dafa 上清靈寶大法 (chapter Santan shejiao pin 散壇設醮品) she occupies the 11th position. In both cases, the Queen Mother is found as the first of the deities after the more "impersonal" Three Pures and the Four Guides (Siyu 四御).

|

The Queen Mother of the West as the Daoist deity "Golden Mother" among the multitude of gods and immortals, Yuan period wall painting (detail) in the Yongle Temple 永樂宮 in Ruicheng 芮城, Shanxi. This is the painting of the inner west wall of the Hall of the Three Pures (Sanqinggong 三清殿). The Golden Mother wears a crown and her head is encircled by a halo (xiangguang 項光). 440 × 942 cm. Source: Zhongguo meishu quanji bianji weiyuanhui 《中國美術全集》編輯委員會, ed. (1993). Zhongguo meishu quanji 中國美術全集, Huihua bian 繪畫編, Vol. 13, Siguan bihua 寺觀壁畫 (Beijing: Beijing wenwu chubanshe), no. 89. |

During the Jin 金 (1115-1234) and Yuan 元 (1279-1368) periods, the Quanzhen School 全真派 emphatically promoted the veneration of the Eastern King-Lord and the Queeen Mother, with the former as the "ancestor" of the line. The Hall of the Three Pures (Sanqinggong 三清殿) in the Yongle Temple 永樂宮 in Ruicheng 芮城, Shanxi, houses a wall painting, showing the Three Pures encircled by eight major deities, among them the Lord of the Way, Azure Lad, Duke of the Wood, Supreme Councellor of the Eastern Flower (Donghua Shangxiang Mugong Qingtong Daojun 東華上相木公青童道君) and the Primordial Lady, Golden Mother of the Utmost Veracity of the Nine Numina with the White Jade and the Tortoise Terrace (Baiyu Guitai Jiuling Taizhen Jinmu Yuanjun 白玉龜臺九靈太真金母元君), i.e. the Eastern King-Lord (Dongwanggong 東王公) and his counterpart, the Queen Mother of the West.

Outside of Daoist belief, the Queen Mother played an important role in popular religion. Various historiographical books mentioned shrines or temples of the deity, where she was implored to bring rain or good harvest. The story of banquets, mainly the peach banquet, were adapted in literature and found entrance in novellas and theatre plays like Pantaohui 蟠桃會 or Yaochihui 瑶池會. The story is also mentioned in the famous romance Xiyouji 西遊記 "Journey to the West".